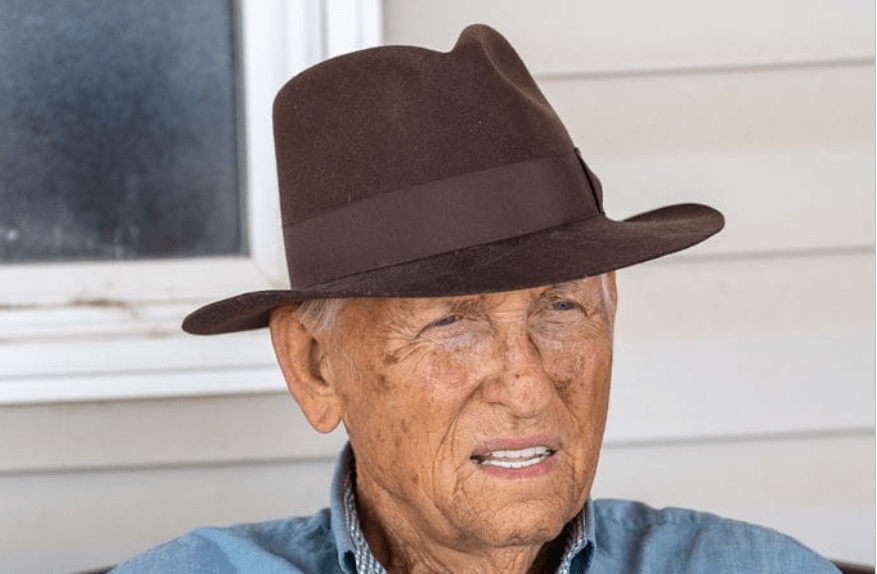

“They made a bumper crop of cotton back on the Panhandle one year. They needed a place to store all that cotton. So they’d take two sticks of cedar, cut just right, so they could stack them on the ground. They had millions of bales that had to have those cedar poles. So Daddy come down and got us, and we got in some virgin cedar and started cutting. They had to be like a 3-inch diameter, about 2 feet long, so we’d load the cut wood on the trailer. We made pretty good money off them. One time we’d have plenty of money, then the next we’re out beating the bush, looking for money. That’s just part of being independent, being free. Horse-trading around, I guess you could call it. There’s nothing guaranteed about it,” drawled soft-spoken 75-year-old, Johnny Kirklin an old school storyteller extraordinaire who lives 2 miles outside of Bangs.

“Growing up in Brady, Texas, there was never any, and there’s still not now, any jobs. So I had to find a way to make money,” Kirklin expounded while slowly stirring a cup of black coffee at the Red Wagon in Brownwood. His sharp, blue eyes flared into the cup as he thought back. “So we made our own jobs, and I grew up doing that, and that’s what I call horse-trading stuff. My dad, he’d go to East Texas. We’d leave out at midnight to avoid the highway patrol, drive all the way to East Texas. I was just 12 years old, and we’d set out to leave the house, so mamma didn’t know that I was driving. He’d pull over and say, ‘I’m gonna lay down in the seat and get some sleep. You get over and drive.’ The truck had a big old steering wheel, I could just see underneath that steering wheel. We was going the back ways, and he’d go to sleeping, and it scared me to death when I’d meet a car on those farm to market roads. We stopped at a truck stop. I was hungry, I’d been driving, and it was just turning daylight, so he said, ‘Pull over here to the truck stop’. I pulled over there, just looking underneath the steering wheel. I was glad not to handle any more traffic, and we went in there. Well I’d never really been out of Brady, and that was a big deal for me to go down there, and the waitress come down, and Daddy ordered his eggs over easy and all that. I’d never heard of it. She asked me, ‘Sonny what’ll you have, how do you want your eggs now?’ and I said, ‘Well I want them cooked.’ I didn’t know there was any other way to have them.”

“We went on down to East Texas from there. We’d pick up at the sawmill a load of ash and shavings. It was my job, after school, I’d run these ash posts through this dowel machine and make ‘em round. I’d bundle ‘em up, ten to a bunch, put them in this bobtail truck and run ‘em out to the big ranches where they were building fence. We got like 25 cents a piece for them, which was big money then. I grew up close to the racetrack in Brady. We’d take the wood chips and sell them over there at the racetrack for the stalls for the horses. Every time they’d have races down there, I’d go down and sell racing programs. You never missed an opportunity to make a dollar around there,” Kirklin remembered.

Storytelling as an art form was once a popular, even competitive, pastime in Texas, during the old settler days of the State’s early history. Tales were woven, some true, some not so much, around fireplaces in the evenings, and the competition was fierce to earn the handle of a good storyteller. Telling tales was a way for settlers to catch up on news and to take a break from the harsh workload and constant dangers presented by the largely unsettled lands West of Austin. Fourth-generation Texan Johnny Kirklin, cowboy, bulldozer man and general jack of trades, can tell stories with the best. He ended up cowboying, he said (not surprisingly) because of the stories his grandfather told him about the life.

“My granddad told me all them old stories about him working on the Slaughter Ranch, way out in West Texas, back in the teens, the turn of the century. He rode to El Paso to join Black Jack Pershing to look for Pancho Villa down in Mexico. He just told me all those stories about him working the big ranches in West Texas and New Mexico. So I grew up listening to all that, and we headed out that way, after Milly and I got married. We went up to Big Lake, there was 125 sections up there, and my grandad come and helped us during roundup. My mother would come out and ride too. Well we moved from that ranch to Six Shooter, Texas, near Fort Stockton. We did a lot of roundup work, bringing in cattle and sheep. We’d spend a lot of time fixing the fences and then fixing windmills. One ranch had 65 windmills. When we wasn’t out tending livestock, we always had a windmill needing to be fixed.”

“We’d have a milk cow. They usually furnished you with a milk cow and one or two beefs a year. We had our chickens and the garden. They’d give you two good older ranch horses and two young green ones to train. I usually took green broke horses and tried to put miles on them. Never, ever let them learn how to buck. My daughter is very good with young horses. I use to take a good gelding and we would snub him with a halter and have a saddle on him. I would pull him around with my daughter in the saddle, snubbed up close so he couldn’t get his head down. That’s how we like to do it. We never want a horse to learn how to buck. You had to go to West Texas to get the bigger money on a ranch. We’d come to town once a month to buy groceries. Milly ordered a course to teach our kids. It was too far to get to any schools. So she homeschooled our kids back before it was cool to do that.”

“We didn’t throw things away back then. We fixed them. Johnny never stops. He never gives up. Sometimes it looks like an impossible situation, he just keeps on and keeps on until it works. He might get discouraged and put it up for the night, but the next day he’s back at it. If something is broke, he doesn’t throw it away,” Johnny’s wife of 56 years, Milly Adams Kirklin, added, stacking up breakfast dishes on the cafe table, while the stories flowed on.

“My grandad was always horse trading,” Johnny said. “He’d go out to West Texas and buy a horse. He used to take me with him, when I was young. He had an old car, like a ‘56 old car, and he’d pull a two horse trailer behind it. And when you go out in West Texas, used to be, still like that a little bit, there might be a big windmill or a rock reservoir right there next to the highway. We’d pull over and he’d make coffee, maybe get some pork and beans, and he’d stake his horse out there and he’d get water to water that horse. He’d lay down in the seat and go to sleep. So that’s how I went into horse trading. I was probably eight or nine years old. I wanted to live the life my grandad grew up in, riding for the big ranches, so I did. Then it got to the point where I needed to make more money, the bulldozers did that, so I got into that work.”

Johnny Kirklin is what author J. Frank Dobie would have deemed ‘out of the old rock’, a continuation of a way of life that is slower, passed down from one generation to the next in the form of tales that keep alive characters and ways of living that were built on a foundation of hard work, handshakes and a wry sense of humor. “He can look right at you and tell you a joke, his face never changes. You don’t know it is a joke,” Milly added.

“A guy I grew up with, over in Brady, he moved to Bethesda Maryland on the East Coast,” Johnny chimed in. “He got in the business of cleaning chimneys. That was a big deal back then. I was working on a ranch down in Lampasas, when he had me fly up there. He sent me the airfare, kept begging me to come up, so I went up there and he showed me the chimney business. So I came home, and we packed our stuff. My friend had some old equipment for me to get started, so we come on and moved off the ranch down to Austin, and I started doing that, cleaning chimneys. It was possible for one person with just two hands to make 150,000 a year doing that. We thought we’d won the lottery. We come right off that wild buffalo ranch to the big city. We couldn’t believe there’d be stores to stay open all night. So we’d clean chimneys and that’s how I got to meet some famous people. I went to one house, and the guy said, ‘You come on into my study here. We’d got to talking a bit, and he was writing a book about Texas. And he wanted me to come in his office. I didn’t know who he was, but he told me he was writing this book. I was worried about turning the money cleaning chimneys, but he sat there and interviewed me for nearly an hour, to the point where I had to go back and make some different appointments because I had other appointments I was committed to that day. I actually went back there to talk to him three or four times. I told Milly, ‘This man here made me miss my appointments because he was writin’ this book about Texas.’ And she said, ‘Who is it?’ I told her and she said, ‘Oh my god. That’s James Mitchner’. She’s the one who told me who it was. That kind of business, you met all kinds of people.”

The check had been sitting on the table for over an hour. The staff seemed ready for us to leave. “I’ll tell you another one,” Johnny said, “about the time I took a trailer load of coons to Lookout Mountain, out in North Carolina. You see back then … ”

First published in TexasLiving magazine, reprinted by permission

***

Diane Adams is a local journalist whose columns appear Thursdays on BrownwoodNews.com