On Monday the Welcome W. Chandler chapter of the Daughters of the Republic of Texas hosted a lecture by Scott Zesch, author of the book “Captured: A True Story of Abduction by the Indians on the Texas Frontier.” Zesch is a native of Mason County, whose great-great-uncle Adolph Korn was kidnapped by the Apache Indians near the Llano River in Mason County in 1870.

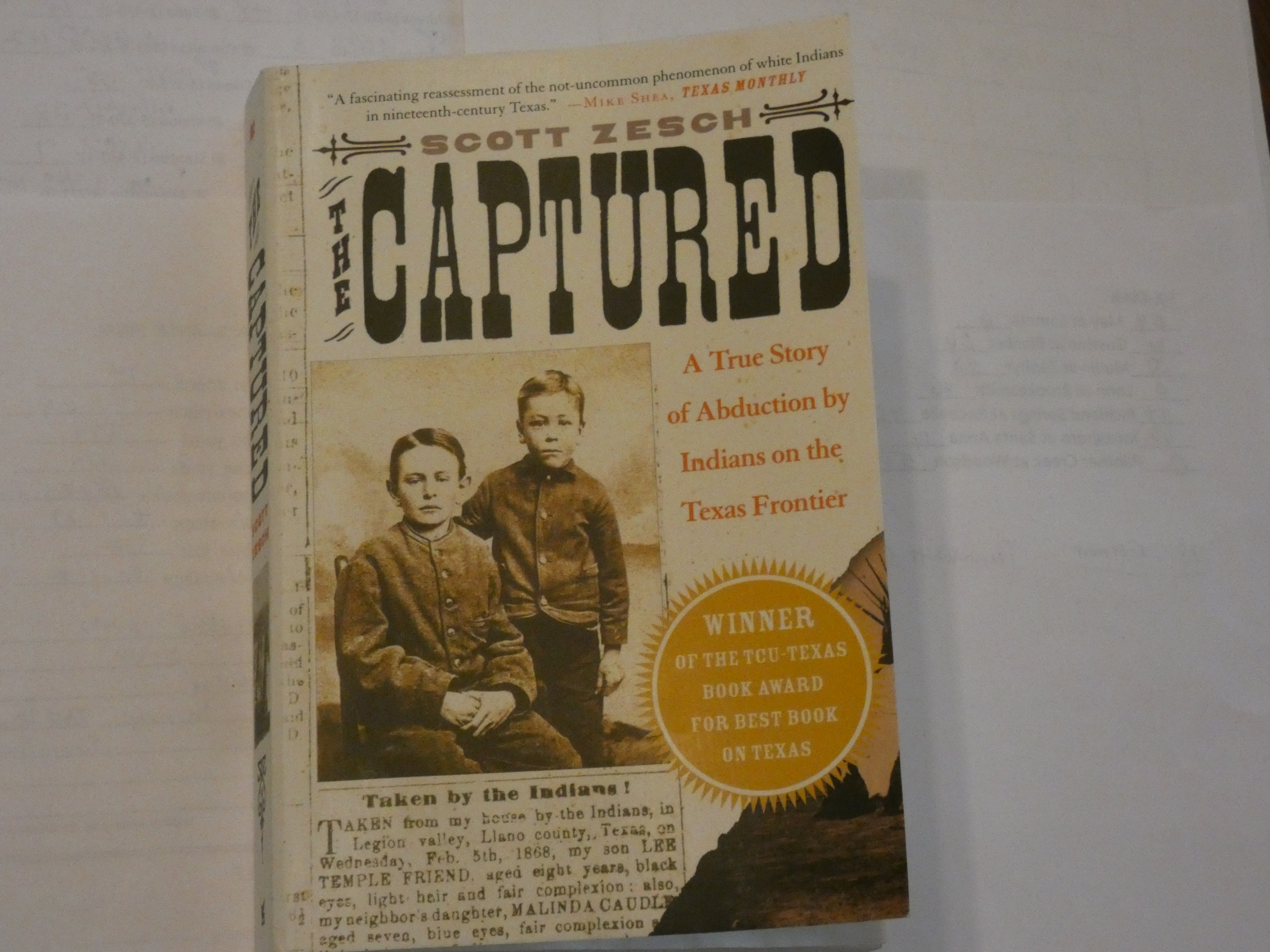

Korn was about ten years old when captured and spent three years with the Apaches before being found and returned home. He did not talk much about his time with the Indians, so there is very little documented detail of his time there. But like most captives, Korn quickly assimilated into the Apache culture, was happy there, and did not want to return to the white man’s world. To learn what his uncle’s experience might have been like, the author Zesch tells the tales of several other persons who were captured by the Indians as children and became “Indianized.” Most of their stories are very similar. (Here is a photograph of Korn taken after his return home.)

One of the earliest kidnappings of a white child by the Indians, and probably the most famous, is that of Cynthia Ann Parker, who was kidnapped at the age of nine by the Comanche Indians near the location of Waco today. She spent over twenty years with the Comanches, married an Indian man and had three children. Her oldest son, Quanah Parker, became the last Chief of the Comanches. She was finally found by Texas Ranger Sul Ross and returned, against her will, to her family. Her story is chronicled in the book “Empire of the Summer Moon” by S.C. Gwynne.

Most of the abductions were done by Comanches and Apaches in either the north-central counties of Parker, Jack, Wise, and Young, or the south-central counties of Burnet, Mason, Menard, and Gillespie. Kidnapping was not new activity by the Indians, they had long kidnapped from other tribes. But when the white settlers moved into Texas in the nineteenth century, they became the target. Zesch said there were two reasons the Indians captured children. One was commercial. The children could be ransomed for cash, or traded for needed items like horses, blankets, etc.

But many of the children were captured with adoption in mind. The Indian population in the South Plains area was never large, but their numbers were dwindling from exposure to European diseases to which they had no immunity. To fight the ever-increasing numbers of white settlers, they knew they needed more warriors. Most of the children captured by the Indians were between the ages of seven and fourteen. Children younger than that required too much care; children older than that were not likely to assimilate into the tribe.

When the Indians captured white children, they rode on horseback for several days — almost non-stop — to the northwest to escape the rescue posse that was sure to follow. The captives were taken to what is now Oklahoma, New Mexico, or the Texas Panhandle. The childrens’ experience was brutal at first, but after a few months they would be adopted into an Indian family, given an Indian name, and treated very well. In almost every case, after a year or so the children had learned the Indian language (while forgetting their native English or German) and adapted to the Indian culture. The boys learned to be expert horsemen and to hunt. The girls were given some chores to do, but spent a lot of time just playing with the other Indian children. None of them had to work hard, like they did on their family farm. Universally they reported that they received bundles of love and attention from their adoptive Indian parents. They were happy. When finally found, few wanted to return home.

Scott Zesch’s book “Captured” is a fascinating read. It can be purchased locally at Intermission Book Shop in downtown Brownwood.