I walked the downtown sidewalks absorbing the city, soaking it in as I walked. The sidewalks are patchwork now, a running diary of the urban decades and here there is (now, in this time) a handicap ramp cut in and the cement is new-looking, and there I see a newish patch where the poles for the modern signs were placed.

That’s one thing you notice on the sidewalks is that the sign poles for parking and general instruction have changed a lot through the decades and you see the metal rings in the sidewalk, rusted monuments, where the ancient poles—critical mandates in their time—were later cut off at the ground, and over there you see newer concrete where someone, because he got a certain work order on a certain day, jackhammered a hole to put in the new pole. That pole has been hit by cars and broken off and repaired above ground ad nauseum. The other day it had been broken off or pulled up and was laying on the ground on the edge of Coursey Park and we could see it from the Bakery in the restaurant and we all shook our heads and said “what the hell is wrong with people?”

Anyway, the bent-up sign imperfectly stands again now on the corner of Baker and Brown and tells people that Brown Street is One Way, even if it does so imperfectly.

In that way, Brownwood is like every other city if you look close enough.

Looking at the sidewalk on a Saturday morning as you walk around downtown you can read a lot of the story and if your brain works just so you can hear the traffic from a time gone by and smell the things that were different, too.

There is a door in the restaurant that leads to what we call the “murder closet.” It isn’t a closet at all, but a narrow passage to an even narrower concrete stairwell that leads down to the basement. It’s all very spooky so we call it the murder closet. For right now we keep mop buckets, brooms, and whatnot in there, but if you push past the buckets and the brooms and the debris and go down those stairs a lot of weird things can happen.

My clothing would not be a problem because I was dressed in my bartender clothes; high-waisted pants and button suspenders and a linen shirt not completely unheard of at the time I’m heading to. Long hair could be an issue, so I brought a gray fedora I found at a thrift store and put my hair up and under the hat.

This place was built in 1909 but it’s been standing a long time so at the foot of the stairs in the basement you can access quite a few different times if you know what you’re doing.

The age of the place and the fact that it had hardly changed made it easier for me to travel back and visit another, earlier Brownwood in the late 1930s. My eyes closed, and thinking myself to be in that time, I traveled to that older/newer Brownwood. It is a weird thing about time travel, you think you are going to an “older” time, but when you get there, everything is newer. The people are younger than you think, too.

Go back to the signing of the Declaration of Independence and you’ll see that the “Founding Fathers” were a bunch of kids, giddy and nervous and rebellious and not as certain as you’d imagine.

I was in the basement of the bank, near the large vault and I didn’t consider until now that this would have been a great plan to rob the place. Or a really bad one. But no one saw me. The basement wasn’t in much use back then (or since then) for much more than access to the huge coal boiler or to the mechanical elements of the elevator. The floor was dirt and coal dust.

I walked briskly around the corner, up to the door that led to the outside stairwell but then realized that I couldn’t do this and not at least check.

Was it there? Of course it was, in 1939.

I turned and quick-walked the length of the basement to the west wall. And there it was.

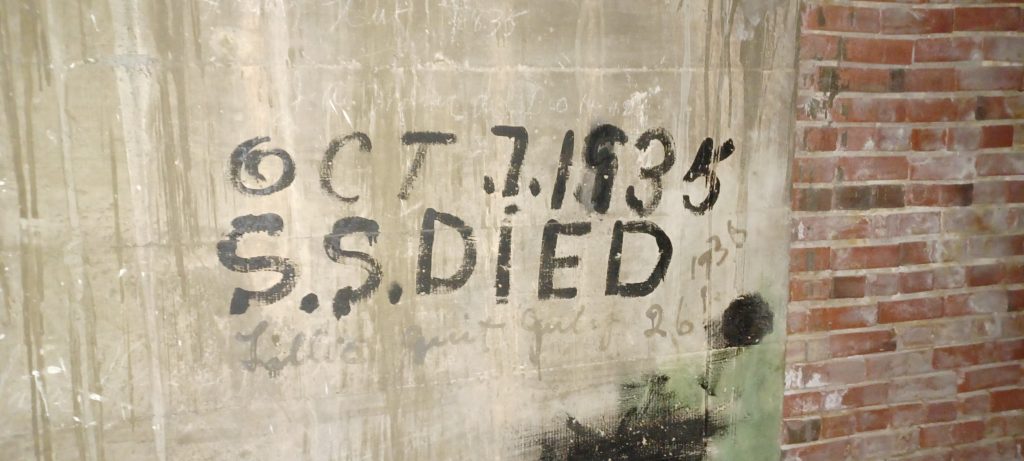

Handwritten in tar or black paint, it seems, in large letters. But there it was:

OCT .7. 1935

S.S. DIED

And under it, in a lighter, cursive hand:

Lillie quit July 26! And the addendum, as an afterthought (1936)

Lillie quit 9 months after S.S. Died. There is a story there. The two announcements are not unrelated, if you see them you can tell. Someday I’ll do the research, but it would be easy enough to find out who died on October 7, 1935 in Brownwood whose initials were S.S.

Satisfied, I decided to leave before someone saw me down there. Back to the door and up the outside stairwell and out into the alley. 1939 was not a time of bank robberies like it would have been in 1909. Security was lax.

I did not stand out too much because of my clothes, and the sidewalk was frenetic with people bustling to and fro, pushing into businesses along Baker. I noticed that most of the businesses had awnings and I like the look, and the cars now are thick as fleas and there is honking as they try to park amid the throng.

Down the street and under the awning of a newer Brownwood Hotel (only 9 years old!) I engaged a merchant in conversation. We stood, arms crossed, against the brick hotel and back out of the way of the crowd. Brownwood was already much debauched at the time, but not as much as it would be in just a few years when 100,000 soldiers would be here downtown too.

The merchant didn’t seem disturbed or surprised that I was not wearing a coat or carrying one or that my watch was probably too large for the time. I think he’d seen crazier things. Neither was he surprised or disturbed when I jokingly told him I was from the future and was just here for the afternoon doing research for a book.

The man, whose name was Xavier Fontineau (originally from New Orleans,) asked me what men were like in my day. So, I told him.

“They wear their undershirts only, or big untucked shirts, and children’s-style short knickers, and go about in bath shoes, and live in slavish submission to both their fears and their appetites. The people hold their own comfort and safety as the highest good and consider freedom a relic to be traded away for safety, or to be redefined daily. They are moved solely by those who manufacture the news, and as an electorate, they are motivated exclusively by these three things: The fear of what government will do to them, or take from them, or their greed for what government will get for them.”

“That sounds bleak,” Fontineau said, “but here with the war coming on. Inevitable. People are very divided. If we do not go to Europe and fight, we will fight here amongst ourselves again. There are two parties who hate enough to kill.”

“There too,” I said.

We went inside and he poured bourbon, not really legal in town, one for each of us. You could get it by prescription and nearly everyone downtown did – one pint a day if you wanted it – and this would make Brownwood even more debauched in the coming war years but probably more fun.

Fontineau told me… “It is called “bourbon” from the county in Kentucky that made the whiskey that my New Orleans liked most. Not because it tasted best, but because the name ‘bourbon’ reminded us of France… of home. It was this thoughtless demand in New Orleans that has made Kentucky Bourbon famous.”

“Some things don’t change,” I said. “At least there’s that.”

Fontineau nodded and we toasted the stupidities that don’t change.

“What’s next?” he asked.

“I reckon I’ll walk over to Brown Street and see the signs and look at the sidewalks.”

“The bourbon will be good for that,” he said.

“I reckon.”

“C’mon back somewhen and tell me about your place and I’ll show you some things wonderful to see.”

“I reckon I will.”

Michael Bunker

***

Michael Bunker is a local columnist for BrownwoodNews.com whose columns appear periodically on the website.