Last week I was privileged to visit Fiveash Cemetery out near Trickham with a great, great-grandson of the Fiveash family. The Fiveash family, together with their friends, the Williams family, were the first settlers in the area now called Trickham. Sources vary a little on the exact dates, but Don King believes the families arrived in this area in 1865. Enoch Fiveash, along with his wife Lucinda and their children, built a home near the location of the cemetery, slightly south of where Trickham is today.

The cemetery is pretty overgrown, with a few old, mostly dead mesquites lending a lonesome feel to it. Don, and my friend and fellow history buff Jen Evetts, and I waded through the weeds to see the crumbling tombstones, some of which were built, as many in early Trickham were, using large slabs of sandstone to form above ground crypts several feet high. The stories we have of these early frontiersmen tell mostly about the hardships they faced living in what was then wild country, and can raise the hairs on your neck.

Local histories state that Enoch Fiveash was a founding. A family in Tennessee supposedly discovered the abandoned infant and named him for five small sprouts of an ash tree growing nearby. After researching the story, Don does not think it is true. “I first learned about Enoch and the Fiveash family as a boy of nine. I stayed with my grandparents a lot in those days at their house on the Brownwood highway north of Brady. That was a long time ago, back before Grandpa Wood died and Grandma moved into town. I remember clearly Grandma telling me the story of her grandfather Enoch being found as a baby in a grove of ash trees, and that he was adopted and named Fiveash for the trees, and that the Indians had left him there or found him or something, that part being a little fuzzy after all these years.” King said.

Regardless of the truth about his birth, Enoch Fiveash seemingly heard about cattleman John Chisum’s outfit, which was free ranging cattle along the Colorado River, and decided to try his hand at it as well. I like King’s creative recreation of the probable route of the immigrants as they traveled to Mukewater Creek:

They’d have passed through the emerging town of Comanche before crossing unceremoniously into Brown County where no more than three hundred inhabitants could be found scattered across the entirety of the county, with only a fraction of them residing in the meager village of Brownwood. They’d have crossed the rudimentary bridge over the lazy, meandering Pecan Bayou into the town itself, with its two stores, log courthouse and perhaps five dwellings. They might even have stayed the night in the relative safety of the village before heading out again at daybreak the next morning, hopefully the last leg of the journey. They’d have noticed how in Brownwood the road split, the upper branch veering northwest to Camp Colorado with the lower branch—barely a trail worn down by cattle drives—angling southwestward along the frontier line.

Enoch would have reminded everyone to stay alert, knowing from experience to not be lulled by the serenity of the fine rangeland. He knew their path could suddenly be crossed by a Comanche or Kiowa hunting—or raiding—party. They’d have crossed the fading paths near the old Ranger Camp Collier, confirming their course. Or joined with the imprints of John Chisum’s cattle herds likewise headed to southern Coleman County.

Onward they trudged until finally reaching Mukewater Creek at its junction with the military road near the little store where the town of Trickham would one day arise.

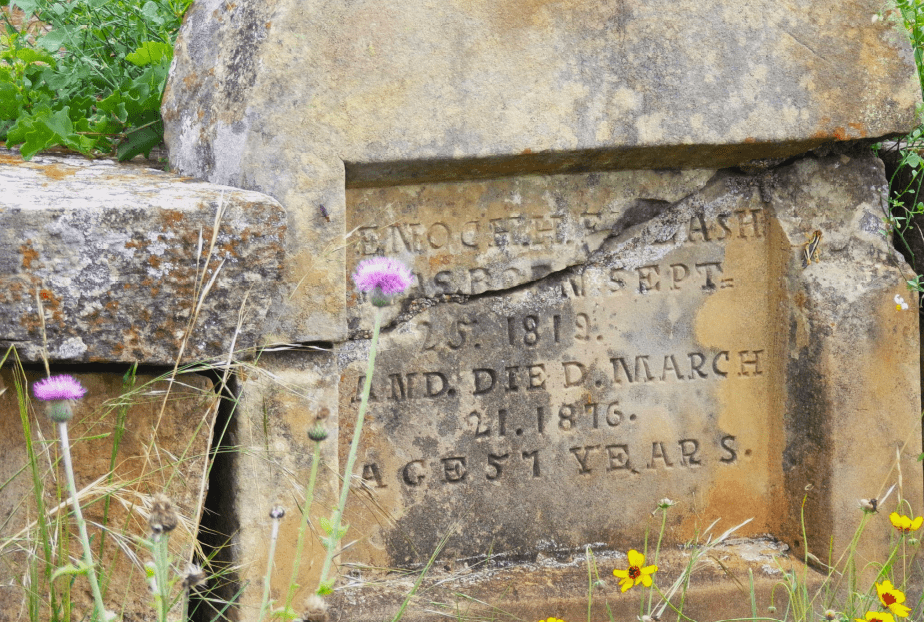

Sudden death, whether from conflicts with the local tribes, disease or violent weather, was an ever present danger. Despite becoming successful in their endeavor to build and homestead land of their own on the open range, Enoch and Lucinda Fiveash suffered a tragic ending in the smallpox epidemic of 1876 that devastated Trickham’s growing population.The conditions they endured are unimaginable. Neighbors and the first doctor that was called were afraid to enter the homes of the sick, and many were left to live or die on their own.

Leona Banister Bruce recorded some details of the event in her book, They Came in Peace to Coleman County. “Enoch seemed to be recovering, but when Lucinda died on March 16, he seemed to lose the will to live. Her grave was dug, and she was wrapped and carried out of the

door and Enoch took to his bed, where he died five days later, on March 21. Meanwhile, son Dick was very ill and the procession of deaths made matters worse. Each new burial was made at a distance from the others, but the neighbors digging the graves would not fill them. As Enoch’s grave was finished, someone voiced the thought that was troubling them all: ‘It doesn’t look like Dick can get well. What do you think about going ahead with his grave while we’re here?’ ‘No, that’s not right,” said Charlie Shield who was helping. ‘It’s not right to dig a grave for a living boy.’ As the days passed, Dick slowly began to recover. Finally conscious and able to

sit by the fire, the lesions began to peel. To prevent possible spread of the disease, it was decided that the three cabins with all their contents would have to be burned.”

These were tough people. Standing there in that neglected cemetery, gazing out at the tangle of wildflowers just beyond the fence, was sobering for me. While Enoch and Lucinda died before their time, many of their descendants still live in the area to this day. Most of us have it pretty easy at this time in history, but I suspect we’re living in the exception, not the rule. Sometimes there is no explanation for the harshness of people’s lives. The silent graves at Fiveash Cemetery testify to a level of hardship most of us can’t comprehend, yet each one of us has a long line of ancestors who went through hell to get us where we are today. I think that is important to remember.

***

Diane Adams is a local journalist whose columns appear Thursdays on BrownwoodNews.com