I’ve written at some length about how you can study and learn a lot of history without being tainted by political narratives, revisionism, and the modern cultural need to re-examine history according to the dictates of the modern samethink cult.

“I know how to watch documentaries! And I have a degree in history from a public university!”

Nope. Documentaries are fun, and sometimes they can be helpful… so long as you know that documentarians have agendas, and that cherry-picking information, data, camera angles, and sound clips is kind of the definition of the job.

You don’t learn history from reading history books or political-leaning agenda treatises. That’s how you imbibe reprogramming tactics designed by ideologues.

“The post-war 40s and 50s are a myth!!”

“The wealth boom and massive growth of the middle class in post-colonial America was a myth!”

“The Belle Epoque was a myth!”

A fun way to identify someone who has a skewed view of history, is that they’re always telling you that some historical epoch was a “myth” because they read a book or watched a YouTube or Googled something that took some outlier negative factoid, amplified it, and recast it as the actual experience of the majority at the time. In order to properly understand any historical period, you need to take a shock and awe approach. This means you have to study a broad cross-section of materials focusing attention on the background settings depicting life and living and not the ideological aims of the piece you are studying.

Let me shorthand this. You have to look at the little things and not the big things. If you want to learn something about Stonewall Jackson’s valley campaign… sure… read the books. But also read letters from soldiers written at the time. Read stuff written by people living there as the armies marched by. Read cookbooks. Historians want to tell you why something happened, and sometimes that means they fudge what actually happened. So, you have to look at the little things and not keep your eyes focused on the big storylines.

Get into the details. (Also, this is how you time travel. But that is for another column… which will be titled: How To Time Travel.)

Zoom in. That is, examine the things they neither thought of, could, or would get away with lying about. A contemporary movie of the 40s may show you a man slapping his wife and convince you that this was normal (that is – widespread and predominant) behavior of a broad cross-section of society, but that scene was written by a writer with an agenda. Telling a story. He needs conflict in his story, and he needs to telegraph information. He needs to save the cat (or kill the cat.)

“Saving the cat” is a scriptwriter’s method of letting you know a character is really a good guy. He may appear gruff and mean – maybe even like he’s a bad guy – but in the first scene you have him save a cat. Now the audience knows that deep down, he’s a good guy. They are rooting for him. Same thing going in the other direction. Have your nice, suburban soccer dad going through his nice, suburban life. But have him kick the cat or be mean to a dog or scowl at a child in the park. Now the audience knows he’s a bad guy deep down. This is how storytellers work.

So, when you’re watching that old movie and you are focused on the part that the writer is making up in order to move the audience in one direction or another, you are drawing conclusions about that time period from information that is designed to manipulate you. You are missing the things that are TRUE in the scene.

What is true in the scene is the dining table and how they switched on the lights. To learn about how a man treated his wife, read thousands of novels, listen to the music (the lyrics will tell you a lot about what people thought,) and read your great grandmother’s letters.

Of course, I’m not saying that you shouldn’t read history books. I’m saying that if you don’t know how to read history books, you will end up with a skewed view of the period. When I was in college and we wrote a paper on some historical episode or epoch, we had to go to the library and always (ALWAYS) “cite your sources.” Anything not cited was not accepted. Same thing now with Google. This means that in that venue, there is a bias towards materials that could get published at the time, and that bias is always coming from the top down and not the bottom up. Citing sources is cool, but it just means that whoever controls publishing at that particular moment in time, controls the story of that age.

George Orwell wrote this about what he saw in the Spanish Civil War:

“Early in life I have noticed that no event is ever correctly reported in a newspaper, but in Spain, for the first time, I saw newspaper reports which did not bear any relation to the facts, not even the relationship which is implied in an ordinary lie. I saw great battles reported where there had been no fighting, and complete silence where hundreds of men had been killed. I saw troops who had fought bravely denounced as cowards and traitors, and others who had never seen a shot fired hailed as heroes of imaginary victories; and I saw newspapers in London retailing these lies and eager intellectuals building emotional superstructures over events that never happened. I saw, in fact, history being written not in terms of what happened but of what ought to have happened according to various “party lines.””

He who controls the printing press gets to control the message. So you have to find the truth in the regular, ordinary scenes of life that no one would think to twist.

Knowing something truly, well, it takes a lot of work. Most people are not willing to work, so they don’t. They take what they are fed, and they live with it as their truth and that’s that.

Read the literature of the time, study books, and watch movies. But you have to learn to come at it slant. You have to see the periphery of the thing and not the thing itself. You can learn the truth by studying the details the people making the content couldn’t or wouldn’t lie about. I’ve used this example in explaining this to people:

There is a movie with Clark Gable (I believe) where he is on the run, accused of a murder. He breaks into a house and is knocked unconscious. To revive him, the woman who knocked him unconscious runs into the kitchen and pumps water from a hand pump that feeds into the sink. Now… one of the things we can learn about this is that at the time this story was set, it was not uncommon for houses to still have hand pumps that pumped water from a well or cistern. And this wasn’t some poor bumpkin’s house. If I recall the movie well enough, one of the inhabitants or visitors of this house is a Supreme Court Justice. And this Justice has to help prove Gable innocent of the crime. The point is that this isn’t some poor farmer’s house. It is a nice house in Washington D.C.

You can get a lot from studying history in this way. Looking at the periphery. Studying the things in the background.

Here are some cool things to know.

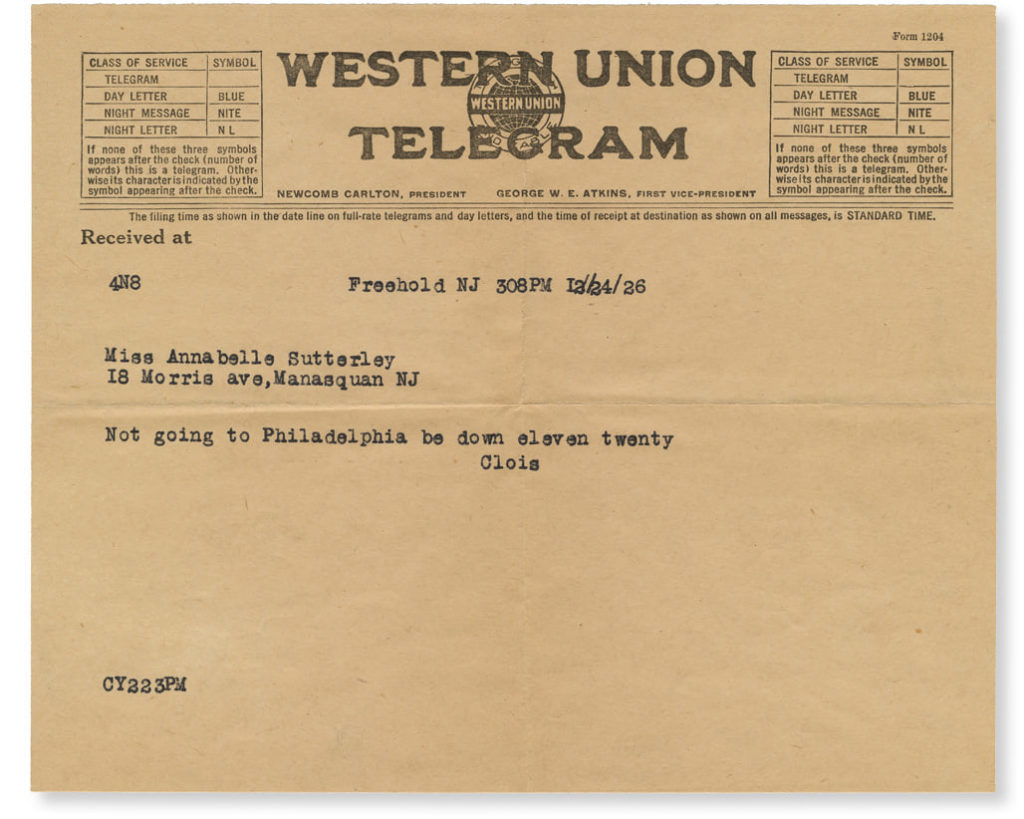

They had “texting” (fast communications across distances that could happen many times in a day) in the 1920s.

When I was young in the 60s and 70s what we would call “instant” or fast communication had actually degraded over about 50 years. In the 1920s it was quite common to send a telegram for just about anything, to just about anyone, just about anywhere. In near real-time. If you were leaving the hotel in Geneva and driving to Prague, you could tell the hotel (hotels had a highly developed information infrastructure) to forward all telegrams to the hotel you’d be staying at in Prague. Or to a restaurant. Or to a home. You could address a letter “General Delivery” and just put the town name, and someone would find you.

And people sent telegrams just to say when they’d be arriving on a train. Just like you’d send a text. “Arriving at 5 pm on the Hawkeye Express” or whatever. You might send a telegram to a hotel in Paris, but the person you were trying to reach had left word that he was going to Bilbao. And when he’d get off the train at Bilbao, the message would be there waiting. It was text messaging without having to carry a device.

But over the next 50 years, telegrams, long-distance, airmail, etc. became prohibitively expensive. When I was a boy, we might know for several days that our grandmother is going to call on Friday at 5 pm. Because she told us in a letter. She was calling LONG DISTANCE which cost a fortune back then. You talked fast. Almost no one sent telegrams anymore by the 1970s except businesses, because telegrams were way too expensive. Things had regressed. What does this mean to your fallacious idea that technology just keeps improving? There are a lot of ins-and-outs to it, a lot of economic realities. But in books written in the 20s, they may be lying about whether Claude was a cheating monster, or could be improperly emphasizing some political point. They may be lying about who was the hero and who was the villain. But they are not lying about a woman in Paris telling the clerk in a department store to charge her purchase of perfume to her room at the hotel. That was a real thing. You could do that.

Also, a fun tidbit. In most cities of any size – and in many small towns and villages – when you arrived in town, you had to fill out a questionnaire for the police. You find this in reading Gogol and in Hemingway too. It was quite common. They wanted to know who was in town and why. If a copper stopped you and you hadn’t filled out the form or checked in with the police, you could be arrested, and whomever you were staying with could be in big trouble too. In many ways, it was harder to hide then than it is now.

Anyway, that’s it for today.

***

Michael Bunker is a local columnist for BrownwoodNews.com whose columns appear periodically on the website.